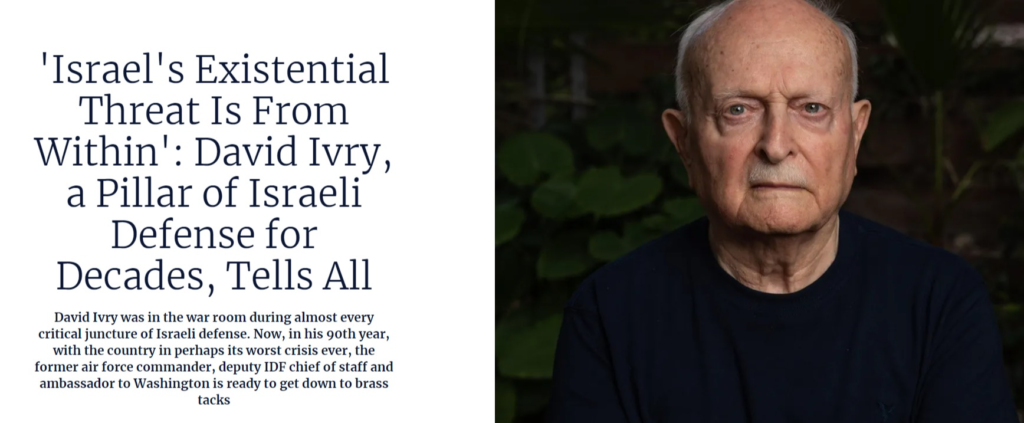

David Ivry was in the war room during almost every critical juncture of Israeli defense. Now, in his 90th year, with the country in perhaps its worst crisis ever, the former air force commander, deputy IDF chief of staff and ambassador to Washington is ready to get down to brass tacks

Feb 23, 2024

https://trinitymedia.ai/player/trinity-player.php?pageURL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.haaretz.com%2Fisrael-news%2F2024-02-23%2Fty-article-magazine%2F.highlight%2Fisraels-existential-threat-is-from-within-a-pillar-of-israeli-defense-tells-all%2F0000018d-d14b-d74b-addf-d77bd0250000%3Fdicbo%3Dv2-gfhDO4e&utm_source=traffic.outbrain.com&utm_medium=referrer&utm_campaign=outbrain_organic&subscriber=0&isDarkMode=0&unitId=2900001646&userId=6d30ef5d-2e43-4ba2-8f85-0f51661b66ef&isLegacyBrowser=false&isPartitioningSupport=1&version=20240312_662c25875a8ec0f1fbcf59787ae641c26cf7ca59&useBunnyCDN=0&themeId=190

David Ivry is worried. “We are entering a war of attrition,” he says in his quiet voice, and sighs. We are speaking in early January, when the Israeli casualty toll was far lower than they are today. “I am familiar with this dynamic from Lebanon, when I served as Israel Defense Forces deputy chief of staff [1983-85]. We are in a place that we conquered, people get used to the situation and we gradually shift from being conquerors to being targets. And this time it’s more serious than it was in Lebanon, because of the ‘Metro’ [labyrinth of underground tunnels] and other subterranean [infrastructure in Gaza]. The question is how long we’ll be able to ride it out, and how you even do that when the government refuses to talk about political solutions.”

We will sink into the Gaza mire?

“I’m telling you that we are already in the Gaza mire. We don’t have a clear solution about what will happen, so we keep saying we’ll be there for a very long time. And we haven’t yet said a word about what’s going on in the north.”

– Advertisement –

Do you share the feeling that we are at one of the most difficult points in our history?

Israel At War: Get a daily summary direct to your inbox

Email *

Please enter a valid email addressSign Up

“Yes. October 7 is a horrific disaster that changed the entire region strategically. The failure is immense. Unforgivable. During Yom Kippur [the 1973 war], the rear was hardly attacked at all. Here we have had communities that were captured, which we haven’t seen since the War of Independence. Within the country itself we have today the largest number of Israeli refugees I have ever seen. But I don’t agree that this is an existential threat. During the War of Independence we faced an existential threat. Until the Six-Day War, we lived with the feeling of an existential threat. Hamas and Hezbollah are not an existential threat. The existential threat is internal.”

Ivry’s lifework has been to forge the State of Israel’s strategic might. In addition to serving as deputy chief of staff of the IDF, the former pilot is best known for serving as commander of the Israel Air Force, director general of the Defense Ministry, founder and head of the National Security Council, chairman of Israel Aerospace Industries, and Israel’s ambassador to Washington. Last September, he turned 89. He doesn’t celebrate birthdays: His mother died when he was quite young on one of his birthdays, and his son Gil, an F-16 pilot, was killed in a training accident on another. Gil’s cracked watch, which was found at the site of the crash, is displayed in a cabinet of mementos in his home in Ramat Hasharon, along with medals and other awards he has amassed during his life.

The weight of the years doesn’t show in him. Ivry is vigorous, active and analytical, and he has a phenomenal memory. He’s married to Ofra – “We’ve known each other since age zero, we were part of the same group growing up. The formal offer to go steady came after I invited her to the ceremony where we pilots got our wings.” During the past year we held a series of long conversations focusing on his life’s mission vis-a-vis the state’s defense and security. Our meetings began in the shadow of the threat of a judicial overhaul that reared its head a year ago and the resulting severe rift that has developed within the nation, over which he has lost sleep.

- The fate of the Israeli hostages depends on Palestinians running Gaza – and Hamas’ future

- MAD in Lebanon: Are we on our way to mutual assured destruction?

- Yes to Biden’s Mideast plan, yes to a Palestinian state, no to Trump

Before October 7 we sat here and you expressed very profound concern.

“I was very apprehensive about a civil war, and I am concerned that it [that threat] will resurface. A civil war is an existential threat. When the regime coup started I became truly depressed. Look, people are constantly talking about unity in times of war and ‘together we will win,’ etcetera. The first thing that should have happened [after October 7] was for the leader to come out and say, ‘I am now canceling the judicial reform – we are all in this together.’ That did not happen. [Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu did not say that. That is significant. In the end, the Arabs helped us at least to stop the reform. If not, I don’t know where we would be today. But the price is very steep. Too steep.”

* * *

Ivry’s tour of duty as commander of the Israel Air Force, from 1977 to 1982, is remembered mainly thanks to one of the greatest successes in that corps’ history: the destruction in 1981 of the Iraqi nuclear reactor, located southeast of Baghdad, some 1,600 kilometers (about 990 miles) from Israel.

“On the very first day I took over, a meeting was set for me with all the heads of the intelligence community in order to assess the reactor that was then under construction,” Ivry relates. “The conclusion was that it was a reactor with military missions that therefore posed a danger. The recommendations were to continue with diplomatic activity so as to induce France [supplier of the Osirak reactor] to terminate its contract with the Iraqis, to disrupt their progress in various ways, and in the meantime to prepare a plan of attack. My thinking from that point on was about how to increase the range of the IAF: When the first F-16 squadron commanders went to the United States in order to bring the planes back, I told them, ‘Tell me what’s the longest range you can get with it [an F-16] in a ground attack.’ They didn’t understand why I was so insistent about that.”

For a few years you and the IAF were preparing to carry out the operation.

“We weren’t the first who decided that attacking a nuclear reactor is permissible. The Iranians tried to attack it twice, and messed it up. The problem was that after each Iranian attack, the Iraqis beefed up their defense. They built high walls, they sent up balloons with iron cables, so that if you flew low you would run into them; they brought in SAMs [surface to air missiles]. It was decided to attack before they arrived at a certain threshold of enriched uranium.”

Breaking news and the best of Haaretz straight to your inbox

Email *

Please enter a valid email addressSign Up

The operation was planned for the spring of 1981. “Daily discussions were held in the IDF General Staff,” Ivry continues. “In the midst of the preparations and discussions [in May], Raful’s son [the son of then-IDF Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan] was killed in a plane crash. He was flying a Kfir, got into a tailspin and crashed to the ground. At the funeral, ‘Eizer’ [Ezer Weizman], who was no longer the defense minister, grabbed me and said, ‘You’re all insane, you can’t do it [attack the reactor].’ I said nothing.”

October 7 is a horrific disaster… but I don’t agree that this is an existential threat. During the War of Independence we faced an existential threat. Hamas and Hezbollah are not an existential threat. The existential threat is internal.David Ivry

You’re the commander of the IAF, and the chief of staff’s son is killed in a flying accident.

“Yes. I was the one who informed him [Raful]. I went to see him in Jerusalem. But Raful comported himself extraordinarily. During the shivah he attended one of the briefings on our mission. He was very worked up. Some of the pilots remember it to this day, it had an effect on them. He told them something like, ‘Everything you know – it’s not worth [keeping] a secret.’ What he meant was to tell them that if they were captured and tortured, they were allowed to say things, there’s no need to die. The feeling was that he was speaking emotionally, like a father.”

The feeling was that the pilots wouldn’t return?

“Part of the coping was through cynicism. In the briefing we gave the pilots dates, so they would get used to eating them. They also had Iraqi dinars. Yigael Yadin, who was a minister under [Prime Minister Menachem] Begin and sat in on the discussions, thought it was a one-way ticket, that it was a suicide mission. Some people thought we were dispatching pilots to a mission along the lines of Ammunition Hill [in Jerusalem, the scene of fierce battles in 1967]. By the way, the original code name of the attack was ‘Ammunition Hill’ – which has a connotation of many fatalities. In the end, we gave it a different name: Operation Opera.”

Were you apprehensive?

“My assessment was that if we could create a tactical surprise – fly low and evade radar until just before entry – we would achieve the goal. My main problem was how to get the pilots home. So I set the time [of the attack] at twilight. Why? Because if on the way back they would fly high in order to consume less fuel, no one would succeed in intercepting them. Iraq and Jordan [whose airspace the IAF violated] didn’t have the capability of nighttime interception back then. It meant that even if someone had to eject, I’d have all night long to bring him back, with helicopters. That meant I also had to maintain helicopters in the area. And Hercules [aircraft] for aerial refueling. And F-15s that [provided cover for the F-16As and] would engage in dogfights in the event of interceptions. And planes for intelligence and EW [electronic warfare] and communications.

“Ultimately it was said that eight planes attacked the reactor, but we had something like 30 aircraft in the air. It was the sort of operation that gave expression to the capabilities of an entire corps, with very few in on the secret over a lengthy period. Until the very end, it was essential that people not know what the goal was.”

Ivry’s collection of memorabilia includes a handwritten note from Chief of Staff Eitan about the timing of the operation, which took place on June 7. “We had an argument,” he recalls. “He wrote, ‘Let’s think about when to attack, maybe on Friday, because that’s also the Muslims’ Sabbath.’ In the end we agreed that it would be on a Sunday. I really wanted Sunday, because all the French workers [at the site] wouldn’t be there, as it’s their weekend, and our goal was not to kill people. Ze’evik Raz and his crew, who led the mission, asked to move up the departure time by half an hour. I decided not to argue. I didn’t really want to explain to them that I wanted to have the whole night for rescues – that’s not exactly what’s psychologically correct to drum into the head of pilots before an attack.”

What goes through your head before the attack?

“The message that authorization had been given for the attack was received on Friday. We were supposed to update the government on Saturday evening. That evening we hosted here, around the table we’re now sitting at, the widow of Ohad Shadmi. He had been the commander of the 109th Squadron, one of our finest, and he was killed in the War of Attrition. These days when I come home, I realize I have to make sure to be fully present. But in that case I was thinking all the time about what else needed to be done. I sat here, but I wasn’t really present that evening.”

You didn’t share your thoughts?

“At that stage, not yet. On Saturday I requested that a mission briefing be held at the base near Eilat. My family was in Gedera and on the way back I collected them and said to Ofra, ‘Tomorrow we are going to attack the reactor in Iraq.’ It was the first time I’d ever done anything like that – usually I would call and speak to her only after the fact, but this time so much had already built up inside me. And the whole time I knew the responsibility rested with me.”

Until then she didn’t know anything?

“Not a thing.”

You worked on it for years, and you couldn’t share?

“Of course not.”

How did she react?

“She didn’t say anything. What’s interesting is that she didn’t sleep the whole night after that. I did. The next day, everything went according to schedule. The planes took off from Etzion Base, near Eilat. I instructed them to take a flight path over Saudi Arabia, for the purpose of deception – so that if they were spotted, they’d appear to flying toward that country. And then I got a call in the ‘Pit’ [IDF headquarters in Tel Aviv] that there was a problem with Hussein.”

Hussein?

“King Hussein [of Jordan]. He’s sailing in the Gulf of Eilat on his yacht that weekend, and calls his staff headquarters and says he’s seen eight F-16s in the air and tells them to go on alert. Years later I met him and we reminisced. He said he was sure the aircraft were headed for Jordan. You have to remember that at the time, warm relations existed between the Jordanian CC [military control center] and the Iraqi CC. And meanwhile I’m waiting. We didn’t see the planes on our radar, because of how they were flying. There was radio silence. So we’re running things from a table in the Pit according to the planned time and speed. But no one actually sees them.

“There was tension. Raful is next to me, sitting quietly. I’m monitoring the situation all the time to see if there’s a reaction anywhere, because that would be a sign that someone had discovered them [the F-16s]. But everything is quiet. Until 45 seconds before the attack, when we hear in the relays that they are preparing to attack. And then control asks everyone to report via radio. Ilan Ramon doesn’t reply because he’s apparently dealing with a high G-force. He was No. 8 in the formation. It took around 30 seconds – a long time – and then he responded, and they all say ‘Charlie.’ That means ‘we all attacked, the target was destroyed, we’re on the way home safely.’ The best code word I could have hoped to hear.

If you’re not serving a policy, you must not launch a military operation. You can’t block an enemy state’s will to achieve nuclear capability. You can buy time, preferably by nonmilitary means. The military option should be the last resort.David Ivry

“Thirty miles before they arrived, I got on the line. Usually the IAF commander doesn’t speak via radio communication. The call sign of the commander was ‘Caesar.’ I said, ‘Caesar here, well done, welcome home, but the sortie ends after landing.’ You have to understand: The adrenaline after something like that is insane, and then, when you head back, you sometimes make mistakes because you’re not paying attention. So they landed safely and returned home to their families that night, and it was all still secret.”

No one was allowed to say anything.

“The agreement with the government was that it would be kept classified. Only if the Iraqis were to announce that they had been attacked, would we admit to it. It wasn’t until after the operation that I grasped how significant it was. The longer you take to admit responsibility, the lower the expectation is of a counter-response. And then I discover that Begin made the announcement over the radio. He hadn’t spoken with Raful or with me. It’s a total surprise to me, because we had all kept it secret. A problem of trust with the pilots began to develop.

“I found myself in a very uncomfortable situation, because I couldn’t say that the prime minister had acted wrongly. Reports reached Begin that the pilots were very angry, so he decided to visit Ramat David [airbase]. We walked around there with the pilots, while the pilots’ wives in the base’s family residences made protest posters against him. Everything got mixed up with the election campaign, which began to shift in his favor.”

(The close election, which ended in a victory for Begin’s Likud party, took place on June 30.)

You brought Begin the victory, actually.

“You could say that.”

The issue at hand today is the Iranian nuclear project. What can we learn from the Iraqi attack?

“The basic question concerns the goal of the attack. The attack must serve the policy. If you’re not serving a policy, you must not launch a military operation. The goal is for an enemy state not to go nuclear? You can’t block their leadership’s will to achieve nuclear capability. What you can do is buy time. If you can achieve that by nonmilitary means, that’s preferable. The military option should be the last resort, because it can deteriorate into war.

“Furthermore, if I can buy time by attacking two to three targets and I gain three or five years that way, then why not attack just three targets? Why do I need to attack 10 or 20? Which is to say that, it’s not the quantity that makes the difference, it’s the goal – how do I gain maximum time and take minimum risks? I think it was a mistake to terminate the nuclear agreement [i.e., for the Americans to renege on the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action]. The goal is to buy time. [U.S. President Barack] Obama did that via an agreement. It wasn’t good enough, but the fact is that Netanyahu applied pressure and [President Donald] Trump withdrew from it – and the Iranians are in a far more advanced state [today] than they were.”

* * *

We go back to the very beginning of Ivry’s story.

“My parents came to this country from Slovakia in August 1934, and I was born a month later in Hadassah Hospital in Tel Aviv,” he relates. “My father was an accountant, from an affluent family that was in the lumber business. He couldn’t find a job, so they moved to Jerusalem, and they couldn’t find work there, either. In the meantime, they started to sell all the possessions they had brought with them – cupboards, candlesticks, whatever would bring in some money. Occasionally he found a job for a few days picking [fruit] in moshavot [farming communities]. After he walked twice from Gedera to Jerusalem on a Thursday night after finishing his farmwork, in order to save a few pennies, we moved to Gedera.

“During World War II, my dad found work with the British, but he was injured when a truck turned over. One foot was shortened by something like 3 centimeters and he started to limp; it was hard for him to work. He didn’t have insurance, there was no compensation, nothing. So my mother began working in workers’ restaurants to support us, and afterward she fell ill with cancer. By the time I was 10, she had already been sick, had recovered, fell ill again, underwent radiation. She died on my 20th birthday, left me like that. On my birthday. Years later, my son Gil was also killed on my birthday. My mother was 53 when she died, I was 53 when my son was killed. Sometimes I just can’t get my head around things like these.”

Gil was killed in 1987 when his F-16 crashed during training. He was 27. Ivry has rarely mentioned the tragedy publicly until now.

“I was the director general of the Defense Ministry at the time,” he says. “After the end of the Yom Kippur war, I often travelled to participate in annual strategic talks with the Americans. Usually I took Ofra along on these trips, at my expense. We flew to New York, she stayed there, and I went on to Washington. On one occasion, during breakfast with the head of the American team, Amos Yaron, the Israeli defense attaché, left the room to take a call from Israel. When he got back he asked me to accompany him out of the room and told me that Gil had been killed. I asked him not to say anything to Ofra – I didn’t want her to hear it from someone else. I flew quickly back to New York, and told her.”

Weren’t you apprehensive when Gil followed in your footsteps?

“I didn’t pressure him at all. He dithered about it, but a big group of his friends went to a pilots course together. At certain stages he wanted to drop out of the course, because he thought he wasn’t suited for it. They spoke to him and he decided to stay on. He was a kid who was used to making decisions by himself. He also left home and rented a place; he wanted to be independent. At first I was really apprehensive, because most accidents happen in those initial years. Afterward, when he was already an instructor, I wasn’t afraid. He’d already learned how to let go. He managed to go on a trip to South America, on furlough, and came back. He had a few more months to serve. He was killed during a training session simulating a war situation, with the pressure of [piloting] a large number of flights. Without knowing it, he exceeded the quota of permissible flights. Unfortunately, he did two more than the permitted number. After that they stopped those exercises.”

After the shivah I went straight back to work. Rabin, who was then the defense minister, met me when I arrived. No one knew it, but we both sat and cried. We cried with tears and weren’t able to speak.David Ivry

You were known for being strict about safety and about investigating accidents in the IAF. Did you go into the details here as well?

“I couldn’t do that for all kinds of reasons. I will say no more than that Avihu Ben Nun, who then commanded the IAF, didn’t even bother to come and explain to me what happened. We decided in the family that we would try to resume life and that each of us would continue working and doing their thing. We had talks with our other two kids about it. We established a fund on behalf of former defense establishment personnel who were suffering from problems, and invested all the compensation money we received, as well as some donations, in it. It wasn’t easy for us, but we decided that we would continue with our lives and would not make allegations, investigate or occupy ourselves with it. Because it wouldn’t help us. It was painful, it was painful.

“All kinds of thoughts occurred to me. Like, I was the one who had brought the F-16 to the IAF and he was killed in an F-16. Every year we have these terrible days ahead of Yom Kippur [because he was killed before that holiday]. We’re like everyone else. What we decided is that we need to neutralize things and go on with life, for the sake of the other children and in general. Becoming depressed doesn’t help anyone. The very fact that you delve into things doesn’t help anyone. You have to come to terms and then start living as best you can. After the shivah I went straight back to work. Because there were a lot of things that had to be dealt with. [Yitzhak] Rabin, who was then the defense minister, met me when I arrived. No one knew it, but we both sat and cried. We cried with tears and weren’t able to speak.”

A decade later, you agreed to head the committee that investigated the helicopter disaster [in 1997, when two IAF transport helicopters collided, killing 73 personnel].

“They really pressured me, I didn’t have any other option. I thought to myself that it was a cruel decision: Not long ago my son was killed, and now you’re giving me an assignment like this – on a committee like this? It was very hard for me. How to remain objective, not to deal with my own baggage. That wasn’t always possible. On some days the sessions were open to the public. One day a young guy came and said, ‘I know the IAF, all of you give your sons privileges.’ I said nothing. Afterward I only asked him what form that took with respect to the helicopter disaster. I think the idea of putting me in charge was that if it was a bereaved father who was involved, it would be perceived as objective. But what I felt was that I was going to my son’s funeral again every day. Those were very rough weeks.”

* * *

Growing up, Ivry didn’t think he would pursue a military career. “The career army wasn’t respectable,” he says. “Being an Egged [bus company] driver was respectable. At the end of the pilots course, Ezer Weizman, who was then wing commander, called us in one by one and pressured us to sign on for a few more years. They appealed to our conscience. There were reports then about the Czech arms deal [with Egypt]. There was hysteria. It’s hard for people today to grasp the distress and the insecurity that existed in this country before 1967. Existential fear. The feeling that Israel would not be able to hang on. Even after I signed on the first time, they kept urging me to stay a little longer. That hadn’t been my intention.”

The Six-Day War – in particular, Israel’s acclaimed, preemptive Operation Focus air strike, which destroyed much of Egypt’s air force on the ground and launched the war – found Ivry at the Hatzor Base. “At 31, I was the commander of a squadron of [French-made] Mirage fighter aircraft; at 33 I was appointed commander of the IAF Flight Academy. The subject of attacking airfields was at the basis of our training. The whole idea was to destroy the enemy’s aircraft while they were on the ground. Almost the entire IAF took part in Operation Focus. The problem was that we didn’t have enough pilots: I think the ratio was about one for every nine planes. For years the force suffered from a shortage of pilots. The achievement in the ’67 war was tremendous, but we also lost a large number of pilots and aircraft. Nineteen aircraft fell on the first day alone, and by the end of the war 25 percent of the IAF’s planes had been hit. That’s a very large number.”

There is little talk about the losses in 1967. They were significant.

“You have to understand something from a strategic point of view. True, we won the war. We destroyed a large number of planes on the ground. But they [the Egyptians] immediately received new – and far better – planes from the Russians, and also surface-to-air missiles, and we were stuck with an embargo and with a diminished air force. We were in a situation of being caught with our pants down. In terms of air power, they didn’t think they had lost at all. From their point of view it was, ‘You destroyed our planes, but our pilots weren’t hurt.’ The IAF emerged from the war with a lot of glory, and it was apparently convenient for it to have the public believe that it destroyed the enemy’s air forces in three hours and all those nice stories – but in practice we were left in a very serious situation. We didn’t have enough pilots or enough instructors.”

Did you also have to deal with loss?

“Of course. I had six pilots who fell, which is a lot for one squadron. And the War of Attrition broke out soon afterward. There was terrible pressure at the [Suez] Canal. The reservists there came under shelling. The activity was intense and the atmosphere was horrific, because the feeling was that at home everything was normal.”

The famous disparity.

“There was a feeling that no one was paying any attention to what was happening there. That people simply fell every day. Many reservists started to feel uneasy. ‘What are we, patsies? We’re still serving in the outposts and they’re hanging out [back home] in cafés and no one gives two hoots about us.'”

* * *

Naturally, in the conversations Haaretz conducted with Ivry before October 7, 2023, significant time was devoted to the war that had erupted exactly 50 years before, on October 6, 1973.

“In May 1973, Benny Peled was appointed commander of IAF and I was appointed head of the Air Division,” he relates. “It was a senior position that involved coordinating long-term staffing and planning work. When I assumed the post I saw an assessment that there would not be a war in 1973 – and there was a budget cut.”

Tell me about the days leading up to the war.

“After Rosh Hashanah [on September 26] I got the mumps. At my age then, it was quite tricky. I’m all swollen, with a high fever. Intelligence reports begin to pile up about a concentration of [enemy] forces in the north. The focus was more on the Syrians than the Egyptians; people in the south thought it was some sort of Egyptian exercise. And I’m laid up in bed. Benny came by almost every evening. On Tuesday [October 2] I told him, ‘Look, we have to mobilize reserves.’ We received authorization to call up 3,000 personnel. The next day I told Ofra: ‘I wish it would rain in the Golan Heights.’ She thought I was hallucinating because of the fever. I told her that if it were to rain in the Golan, the tanks’ ability to navigate would be very limited, so there might not be a war.”

One thing I wanted to do as IAF chief, was to reduce the number of losses. Peled’s approach was to attack at any cost, that if you sign up for the career air force you can die and it’s fine. What is “at any cost”? I always think about how I can leave people alive.David Ivry

At this stage you already understood that we were headed for war.

“Yes. And my problem is that I grasp that we aren’t prepared for it. On Friday, Benny assembled all the base commanders at Sde Dov [airfield near Tel Aviv]. That was unusual, of course. On Friday, the eve of Yom Kippur, everyone is usually on leave. He said, ‘I estimate that there will be a war tomorrow, and I am asking the government to authorize a preemptive strike.’ Some of the commanders took this very seriously, others thought it was just part of some exercise. Each according to his own personality. The next day, Benny summoned me to the Pit at midday. I was still completely swollen, on pills, feverish, everyone was afraid get close to me.

“We took the intelligence update from that morning, which stated that the war would begin at twilight. That was very significant, because Benny thought he would still have time to hold another discussion. He said that in the meantime a preemptive strike hadn’t been authorized. So we started to unload the ammunition from the planes and to convert them into an array that could be used for defense purposes. And then, in the middle of the unloading, the war started. I hurried to the Pit. We were told to scramble the planes. Some of the scrambled aircraft were armed for attack and dropped their payload in the sea. Where were the planes being scrambled to? No one knew.”

You were taken by surprise.

“Yes. But take note: It was a strategic surprise – because we had been told that the war would not take place until 1975 – but it wasn’t an operative surprise, because already a few days earlier everyone thought there actually was going to be a war. No one knew at what time, and we didn’t know whether it would be precisely on Yom Kippur, but we knew that it was coming. In other words, there was information, there was no internalization [of it]. And that is one of the most difficult things in all wars.”

Among the documents in the meticulously ordered archive Ivry maintains in his study are various summaries of the Yom Kippur War. He led an investigation of it immediately upon its conclusion. “All told, we conducted 11,200 sorties in the war and we lost 109 aircraft,” he says. “That is a very steep price. That war had far-reaching consequences on both sides. I’ll give you an example. When I became commander of the IAF [four years later] I needed base commanders. The natural candidates were the war’s squadron commanders. And they had been killed. The principal burden was on the ranking personnel, the veterans. If you dispatch a formation to attack a convoy in Iraq at night, it’s led by a lieutenant colonel. Many of them had been simply killed.”

And you knew them all personally.

“Of course. Most of them had been cadets of mine in the flight academy. And when the war ended, all the fears were first of all for the captives and the missing-in-action. Regarding about 30 percent of them, we didn’t know whether they were alive or dead. That created very tough situations in the families’ residences on the bases. The main effort was to clarify who was alive and who wasn’t, where they were being held captive and what their condition was. Afterward, when the captives were returned, we interviewed each of them personally. There were more than 40. Some had been harmed physically, most underwent torture.”

In 1975, Ivry left to pursue a B.A. in aeronautical engineering at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, which he completed. Two years later he became IAF chief. “I took over on October 29,” he recalls. “I was excited, but I am one of those people who are less happy and more worried about the future. That’s my nature. One thing I knew I wanted to do, was to reduce the number of losses. Benny’s approach was to attack at any cost, that if you sign up for the career air force you can die and it’s fine. I saw that approach even when his son ejected himself from an aircraft in the war and he was sitting next to me. That is not part of my values. What is ‘at any cost’? I always think about how I can leave people alive.”

* * *

Exactly a year after the attack on the Iraqi reactor, the Begin government launched the first Lebanon war. In contrast to the army’s ground forces, the IAF under Ivry’s command emerged from the war with a major achievement, whose implications were far-reaching. Some say they were so far-reaching that they contributed to the fall of the Iron Curtain and the collapse of the Soviet Union a decade later.

Ivry: “On June 5, 1982, I came out of a cabinet meeting and wrote myself the following note: ‘The government decided to task the IDF with the mission of removing all the communities in the Galilee from the range of the terrorists’ gunfire. Name of the operation: Peace for Galilee. During execution of the operation the Syrian army is not to be attacked, unless it attacks our forces.’

“I was very pleased that we were told to avoid striking the Syrians,” he continues. “Not everyone was pleased, there were some who wanted an all-out war. But it was clear that it could deteriorate into that very quickly. And in fact, from the third-fourth day there was friction with the Syrians. Every evening we went up to Northern Command. At our briefing on the evening of Monday June 7, we were told that the next day our forces might reach the Beirut-Damascus highway. I received intelligence to the effect that the Syrians had spread their surface-to-air missiles out in the Golan Heights. We had gotten to the point where they had 19 SAM batteries in the Lebanese Bekaa. At this stage I pressed for authorization to attack.”

This was Operation Mole Cricket, aimed at destroying the Syrian SAMs.

“Yes. There was high tension. From the moment we started, everything proceeded quietly. I was in the control center.”

Describe to me what it looked like.

“There’s a hall with a large black table in the center, with a map of the whole Middle East, on which little towers stand. Each represents a structure and has a certain call sign and code, both yours and the enemy’s. You see them all. We started to attack at 2 P.M. The Phantoms attacked battery after battery and returned home. And then you see the Syrian side emptying out. No planes. I also have an electronic monitor with light bulbs denoting the SAM batteries. When a battery stops functioning, its bulb goes out. And gradually I see all the bulbs going out. I already feel just fine. And panic is starting on the Syrian side. They scramble aircraft, but we destroyed their radar so they [their pilots] can’t see anything.

“And then I am able to dispatch the patrol forces that are waiting for them in three places, to shoot them down. The control center continues to be enthusiastic. Now, what is the problem here? That enthusiasm is not good. I didn’t let any of them give pursuit to Damascus. To cross the border. To give the Syrians an excuse to enter into a total war. We downed 26 of their planes in 30-40 minutes. Without losing a single one of our aircraft.

“When I realized that the goal of destroying the batteries had been achieved, I gave the order to stop and to bring our aircraft home. Some of them still had their payloads, and people were angry with me afterward. But at that stage it wasn’t worth my while to lose a plane, or to enter into mass dogfights. When the Syrians scrambled more planes, I said to the people in the control center: ‘Wait, let them get farther in, I want captives.’ We downed and took captive nine pilots that day. So that now I know that if things slide into a general war, I have bargaining chips in my hand. The next day I went to see the men in captivity, to tell them not to be afraid, that it’ll be alright. They were in total shock.”

Where did you meet them?

“In a Shin Bet [security service] facility. Some were wounded. All were in a state of shock. I still have their photographs. There was one colonel and three or four lieutenant colonels. One was from the Assad family.”

In December 1982, at the age of 48, Ivry concluded his tour of duty as IAF chief, retired from the IDF and was appointed chairman of Israel Aerospace Industries. Two months later, however, the findings were published of the Kahan Commission, which investigated the massacres in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps during the war in Lebanon. The panel recommended terminating the term of Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan, and – pressured from all sides – Ivry agreed to a two-year appointment as head of the General Staff’s Operations Directorate and as deputy of the new chief of staff, Moshe Levy. Afterward Ivry retired permanently from the military, returned to IAI, and in 1986 was appointed director general of the Defense Ministry, a position he held for an entire decade. “It was a kind of ’emergency order’ for me,” he says.

That was a very long term, unparalleled.

“I thought I would do it for two years. After that, they said every year: ‘Stay on a little longer, we need you.’ When I took up the position, I discovered that I was supposed to cope with a lot of things, some of which I wasn’t even aware of: Vanunu [the nuclear whistleblower]; closure of the Lavi project [to manufacture an Israeli warplane]; the Pollard affair; Irangate; the Rami Dotan case [involving corruption in the IAF]. Stressful times, a lot of work with the White House on sensitive issues. I felt like was in a china shop. Afterward came the Gulf War.”

Most of your years as director general were under Defense Minister Rabin.

“We had a special relationship. Every Friday we had a one-on-one work meeting to discuss things and air problems. Sometimes we talked about very secret or strategic affairs, and then brought someone else into the discussion. We met on the morning of Friday, November 3, 1995. I told him, ‘Look, I’ve been on the job for about nine years already, it’s time to move on.’ He said, ‘You’re right, but I need you in the civil service. What would interest you?’ I mentioned a few options, and he said, ‘Let’s think on it a little, come to me on Sunday and we’ll see what to do.’ From there I went to a team-building event at the Defense Ministry. On Saturday night, I got a call telling me he’d been assassinated.”

How did you react?

“The first thing that was clear to me was that I had to remain in the system. And the second thing was the concern for peace. Not that Oslo was ideal. [Yossi] Beilin and [Shimon] Peres pushed Rabin to do more than he wanted [during those negotiations], and he also personally loathed [Palestinian leader Yasser] Arafat, at least at the start. But in the end, I believed that under Rabin’s leadership the peace process could progress, and that after the assassination it might collapse. I wasn’t sure that the other leaders would succeed in moving it forward. My feeling was that the toughest blow was to the young generations, who felt that something was about to change here. A hope was broken.”

* * *

Immediately after October 7, Ivry called me. It was urgent for him to warn in detail about the potential trap of a ground operation in the Gaza Strip. About 100 days later – as reports came in of a large number of IDF fatalities, due to the collapse of two buildings that had been targeted by Hamas RPGs – I returned for another series of conversations.

There is no such thing as an impasse. It’s true that today it will take longer to resolve the situation… But in the end the solution is the demilitarization of a Palestinian state that will exist alongside us.David Ivry

“Everything you predicted is happening, one by one,” I said.

“Unfortunately, we are deep in the Gaza mire,” he replied, “with no reasonable way out. Not for our hostages, either.”

Must we bring them back at any price?

“‘At any price’ sounds pretty populistic. There is a price that no one will be willing to pay. Therefore, the real issue here is of the magnitude of the steep price – and I emphasize – steep – that we are willing to sacrifice. I’m among those who think that terrorists with blood on their hands belong to the category of those to be freed in the difficult situation we find ourselves in. The release is a critical matter. Time will allow the terrorists who will be freed, or the dangers they may pose in the future, to be dealt with – of course, if there will be proper leadership. As I see it, a solution of [averting] immediate danger takes precedence over one involving long-term danger.”

For almost your entire life you have been occupied with building up Israel’s strategic might. Could it be that we are simply not as strong as we thought?

“There are all sorts of wars. There are spheres in which we are very strong. When it comes to big wars we have very good responses. There are realms, however, in which we are not strong enough, such as guerrilla or terrorist warfare. We are pretty much in control in Judea and Samaria, and despite that, we don’t have a sufficient response [to what goes on there]. Why? Because it’s a matter of religious ideology, of millions of people that you’re ruling. There’s nothing you can do about it. You can’t threaten a suicide bomber with the death penalty. The real solution, at the end of the day, is a resolution of the Palestinian question. It’s impossible to escape that.”

You accompanied Rabin at talks on the Oslo Accords.

“Yes, on Friday mornings the delegations that returned from Oslo came in to update him. I would meet up with him afterward and find him anxious, turning red with rage: ‘Again they didn’t listen to what I told them.’ I will say with delicacy that Rabin often felt he had been manipulated – whether justly or not, I have no idea. But the feeling was that he was being maneuvered, that they [his interlocutors] weren’t carrying out what he wanted them to do, which as I understood it was originally more or less in the direction of the Allon plan [involving annexation of certain parts of the occupied territories, with others being offered to Jordan]. It wasn’t by accident that we got to the point at the White House, before the signing of the accords, when Rabin refused to shake hands with Arafat and was convinced to do so only at the very last minute. It was a very fraught process.”

But overall, did you believe in the [diplomatic] process with the Palestinians?

“We thought that Oslo wasn’t a good enough plan. But no one can say whether Oslo has been a success or a failure, because it was never given a chance. In the end, it’s impossible to evade this; it has to be resolved. Agreements can be made with other countries, but by making peace with Saudi Arabia you don’t finish with the problem.”

Is there a solution, or have we reached an impasse?

“There is no such thing as an impasse. It’s true that today it will take longer to resolve the situation, because Palestinian education [against Israel] and incitement really have deepened. And on the Israeli side, too, many fewer people believe in the two-state solution. But in the end the solution is the demilitarization of a Palestinian state that will exist alongside us. In my opinion to live with such a demilitarized Palestinian entity is reasonable.”

The fundamentalist stream has gained a lot of strength in Israel, too. Look at the recent conference about resettling the Gaza Strip and encouraging a [Palestinian] population transfer.

“Let’s start with the emotional point of view. No consideration is being given to the feelings of part of the nation, [those of] the families of the hostages in Gaza, of the soldiers fighting there. They are people who keep shouting ‘Unity! Together we will win!’ but the conference you mention is the biggest example of anti-unity that I know. It’s separation, a rift par excellence. The second thing is that the timing is simply bad. The whole world is watching now, wondering whether to let Israel continue fighting. So you hold a gathering in which you say, ‘I want to fight to the bitter end.’ You organize a gathering that will hamper you in fighting to the end. It’s absolute stupidity!”

Well, Ivry, what do we do?

“The polls show that there is no confidence in the government at all, and the degree of personal trust in the prime minister is only being eroded. During a time like this there is no alternative but to hold an election. It has nothing to do with the war situation. Over time, there must not be a situation of no confidence between the nation and the government. It’s absolutely unhealthy. It creates a situation in which the government doesn’t care about the nation because it see that the nation is not with it. So it [the government] does something that is not good for the nation, the nation’s confidence in the government drops even lower, and it’s a slippery slope. So there is no alternative, despite the war, but to hold an election. The sooner the better.”